14/04/2022

RESEARCH INTO AMATEUR MOVIE-MAKING

From the outset I wanted to shoot with vintage equipment as well as feature it on screen, fully functional and actively recording. And so, Hole in the Head is a smorgasbord of retrograde media formats and technology. All of the processes of visual disintegration and special effects were achieved manually, in an authentically analogue way either by direct chemistry, circuit bending, laser cutting or explosives! Many scenes are created on VHS, VHS-C, Video-8, Hi8 tape; super-8mm and 16mm motion picture film, as well as 35mm and 120mm still film with slide and acetate presentations- in addition to one-eighth inch and quarter-inch audiotape.

In my films, the material format itself is a site of great narrative potential and, therefore, the migration of material from one format to another becomes a dramaturgical act. Hole in the Head takes this one step further, assigning both narrative possibility and formal meaning to each moving image format only to obliterate it in an attempt to mirror the missing time and broken narrative of our protagonist’s past. To achieve this, I wanted to think and shoot like the amateur moviemaker of yesteryear. This led me down a rabbit hole of research and a process that began with a question: what amateur/home movie technology from 1960s-90s era remains functional today and how could I get my hands on it?

RESOURCES

At this juncture, I should flag that I use the term ‘amateur’ here in the truest sense, as the definition of those who create films outside the ‘paying’ or ‘for-hire’ professional circles; those who create films out of a passion and curiosity for the medium itself. Perhaps today, we might prefer to use the term ‘artist’ in order to describe these practitioners. Regardless, there is a proliferation of craft and talent among the amateur filmmakers of 1930s-1980s Ireland- the Horgan brothers, Terence McDonald, Margaret Currivan, Jan de Fouw, J.J. Tohill, Desmond Leslie, Letitia and Naoimi Overend, John J. Jennings, the Holy Rosary Sisters or clergymen Monsignor Reid and Fr. Delaney. A filmmaker of particular interest to me is novelist Michael Farrell who, shooting in Wicklow with Maureen O’Hara née FitzSimons in her first on-screen role, filmed the very same rural stretches and backroads as myself though seventy years earlier.

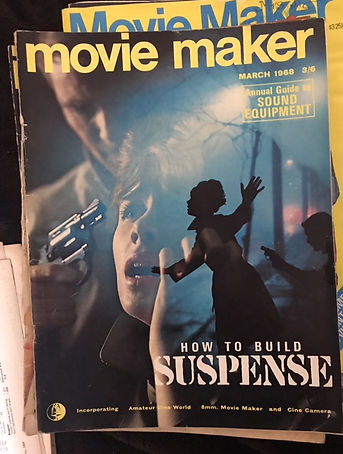

To inaugurate my journey, I collected several printed resources available to the amateur filmmaker of yesteryear. This stepping stone would lead me through a matryoshka of early publications subsumed by 'trendier' publications. I found myself contacting film archives, forums and cold-calling private collectors in order to acquire information, resources, and to piece together the history of various publications.

Initially, I managed to acquire scans from Amateur Cine World, a popular filmmaker magazine that ran from 1934 until 1967. Within its pages, I found traces of Miniature Camera World, another amateur filmmaker magazine that was incorporated into Amateur Cine World in 1944. Up until then, Miniature Camera World was “the only journal solely devoted to substandard cinematography”, a statement I find particularly appealing. In addition to these publications, I found physical copies of 8mm Movie Maker, Cine Camera, and Amateur Movie Maker. Similarly, these were journals dedicated to surfing the wave of everything small gauge- including cameras, projectors, news and reviews on the latest domestic print releases, and general tricks of the trade. In 1964, these publications were merged to create the legendary Movie Maker magazine, not to be confused with the equally important American publication of the same name founded in 1993. From 1964 until 1985 Movie Maker ran as a standalone publication until it was absorbed by the then-popular publication, Making Better Movies, at which stage we drift into the world of Betamax and VHS.

DIY TECH

From these resources, I was able to map certain habits of the small gauge filmmaker and later, the videomaker. DIY techniques in model making and set building or in-camera techniques such as speed variation; backwinding and multiple exposures for in-camera composites; sound adaption; lens adaption; home processing, etc, would forge popular trends among amateur filmmakers using cine-film across the decades. Many tricks outlined across the thousands of pages continue to astound. For example, creating the illusion of clouds passing a moon-lit sky using nothing more than a flashlight and a sheet of glass blackened by candle flame. To create a rolling bank of fog, invert your camera and place a lit fish tank between it and your rear-projected image- then inject the tank with milk. Voilà.

A great number of filmmakers are listed among the hundreds of editions, including the fantastic Roy Spence (described by myself on behalf of the Irish Film Institute as "Ireland's answer to Roger Corman") and the great Bill Davison (described by Glenda Jackson as, “the Ken Russell of the amateur film world”). Both are masterful filmmakers in their own right and their respective filmographies are available online or by request, either through the Irish Film Archive (IFI) or the British Film Archive (BFI). Spence and Davison had regular appearances in Movie Maker, the former sharing expertise on practical and in-camera effects, and the latter penning regular reviews of 8mm movies for collectors in a regular column titled Bootlace Cinema.

By following the legendary “Ten Best” competition, which began in 1948 and continued through to the early 1990s, one can see an explosion of talent and fascinating use of techniques. See Tony Rose’s Coming Shortly (1954) or Stuart Wynn Jones’ “Ten Best” winner Short Spell (1955), for example.

Above: Hand-cutting and editing super-8mm sequences for Hole in the Head (2021, CineStill 800T, 35mm)

WHAT WE DID

The super-8mm shooting and editing process for Hole in the Head explores various techniques drawn from the aforementioned research, making particular use of speed-ramping, back-winding and double-exposure, as well frenetic in-camera editing. A total of three super-8mm cameras were used (two Braun Nizo 801 Professional models and a Canon Auto Zoom 814) across reversal and negative film stock. Cartridges were removed mid-shoot and marked to resume later in order to facilitate our non-chronological shooting schedule. White or burnt-out frames caused by removing the half-spent cartridge were spliced out later if undesired. In some situations, while shooting super-8mm and 16mm, the unexposed reels were hazed with torches, exposed to daylight or, in the case of creating a specific number of exposed frames, the viewfinder was hazed while the magazine was wound forward frame-by-frame to create a speckled pattern of blown-out interruptions.

In-camera editing combined with sudden costume and location changes were scripted with time-jumps so as to mimic how home movies would have naturally manifested. This would become an essential part of demonstrating a sense of lost or missing time as experienced by the protagonist. At later stages, this process would begin to mirror a deteriorating mental state, a form of foreboding or pathetic fallacy active on the material film itself.

Sequences were planned and blocked with actors both filming and performing with the active cameras. After photochemical processing, the material was reviewed and organised by scene. It was then subjected to burial; abrasion and corrosion by chemical mix. This footage was then cleaned and hand-edited using a super-8mm viewer prior to a 4K (10-bit LOG DPX) scan at CineLab London. While chatting over some technical requests, a lab assistant inquired about some of the cleaner material: “Where did you find this?” to which I responded "Oh, we shot that". So, I suppose that was good feedback!

If you are Dublin-based and curious about this research material, I donated all my editions of 8mm Magazine, in addition to a complete run of Movie Maker Magazine, and a complete run of the vintage Boy's Cinema publication to the IFI Irish Film Archive. Boy's Cinema is a fun publication that consisted of movie star profiles and film scripts adapted to a story paper format. The films featured were mostly 'B' pictures and their stories were often serialised across many issues. Boy's Cinema ran from December 1919 to May 1940 for 1063 issues.

Many thanks to Roy Spence, Joseph Bernard, James White, Kassandra O'Connell, Leo Kennedy, Michael Higgins, and the techs at Kodak Lab + CineLab UK.